Sony RX100 V review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

In depth

The Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V is a high-end compact aimed at enthusiasts. Announced in October 2016, it’s the fifth in the RX100 series, which has deservedly become one of Sony’s most successful product lines, packing a larger than average sensor and high-end features into a relatively pocketable body.

The RX100 V keeps the body, tilting selfie-screen, popup XGA OLED viewfinder and 24-70mm f1.8-2.8 lens of the earlier Mark IV, while the stacked 1in / 20 Megapixel sensor still offers 4k video and a wealth of slow motion options at 240, 480 and 960fps. Sony has however upgraded the sensor with 315 embedded phase-detect AF points covering 65% of the frame which allow confident refocusing for stills or movies. By including the front-side LSI which debuted on the A99 Mark II, the RX100 V also doubles the slow motion recording times and increases its burst shooting speed from 16 to 24fps with continuous autofocus and a buffer of 150 shots. The Mark V also supports Eye AF in AF-C mode which is great for portraits when the subject’s not still.

Like the Mark IV before it, most of the major upgrades concern the sensor. Sadly there’s still no touch-screen, and unfortunately the slim body can’t accommodate the more convenient viewfinder housing of the RX1r Mark II – so it’s still a two-step process to open or fold back again. But there’s no denying the Mark V is an extremely powerful compact, and the addition of phase-detect AF has taken it beyond rival 1in models, albeit at a high price tag. Has Sony taken the beloved RX in the right direction? Find out in my review where I’ll compare it against the Mark IV and a variety of 1in rivals, including the more affordable Panasonic Lumix LX10 / LX15.

Note in July 2018, Sony announced a mild refresh to the RX100 V, called the RX100 VA. This model gets the new processor and menus of the RX100 VI and like that model also loses the PlayMemories downloadable apps, although it is otherwise identical to the original Mark V reviewed here. Going forward, the RX100 VA replaces the original RX100 V and is the model you should look for when ordering.

Check prices on the Sony RX100 VA at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V video review / podcast

In the video below, Doug Kaye and I discuss everything you need to know about the Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V! I also have an audio podcast of this discussion below or you can subscribe to the Cameralabs Podcast at iTunes.

Check prices on the Sony RX100 VA at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V design and controls

Sony’s Cyber-shot RX100 V shares exactly the same body as its predecessor, the Mark III. As such it measures 102x58x41mm although Sony quotes the weight a few grams heavier at 299g with battery. Like other cameras in this category there’s no mention of weather-proofing but I think as Sony gradually increases the price point of the RX100 series, there’s potential for a formal degree of ruggedness.

Physically it’s closest in size and weight to Canon’s PowerShot G7X II and Panasonic’s Lumix LX10 / LX15 which measure 103x60x40.4mm and 106x60x42mm, and weigh 304g and 310g with batteries respectively. Coming in slightly larger is Panasonic’s TZ100 / ZS100 at 110x64x44mm and 310g, but in-person all these models are essentially in the same ballpark. As such they’re neither the slimmest nor lightest compacts around, but they will all just about squeeze into trouser pockets. Just before I continue, remember the Sony RX100 III / IV / V and Lumix TZ100 / ZS100 all feature built-in electronic viewfinders whereas the Lumix LX10 / LX15 and G7X Mark II do not. If you’re after something smaller and lighter but still with a decent-sized 1in sensor, you should consider Canon’s PowerShot G9X which sacrifices some zoom range and aperture and the ability to tilt its screen to achieve an impressively compact size of 98x58x31mm and weight of just 209g – understandably there’s no room for a viewfinder in there either.

Like its predecessors, there’s no grip on the front of the RX100 V, only a smooth flat surface. This leaves your right middle finger sliding a little on the front and leaving almost all of the purchase to your thumb on the rear. Again like the Mark IV, there’s a small raised and textured area on the top right of the rear for your thumb to push against. It’s minimal, but if you’re holding the camera with both hands, you can do so pretty securely.

I do understand Sony likes its smooth aesthetics, but there’s no denying a defined grip on the front helps with comfort and stability. Of all the models I mentioned above, Canon’s PowerShot G7X II takes the lead with its substantial, rubber coated front grip. Then the Panasonics follow with minor ridges on the front.

But help is at hand if you desire greater purchase on the RX100 V: Sony offers the optional AG-R2 grip for $15 and as before Richard Franiec sells a selection of custom grips for a variety of cameras including the RX100 series for around $35. Meanwhile if you want to dive with the RX100 V, there’s Sony’s MPK-URX100A housing which costs around $330 and works with any of the RX100 series to depths of 40m. If you want deeper still, there are high-end third party options available including the Nauticam NA-RX100V, rated to 100m albeit costing roughly the same as the camera itself.

Turning to the controls, the mode dial, power button and shutter release with its surrounding zoom collar are all flush to the top surface, unlike Canon and Panasonic which perch some of their upper controls on top. The benefit to having them recessed on the Sony is there’s less chance of them turning by accident when removed from a tight pocket or bag, and it also contributes to a smaller overall form factor.

Access to the mode dial and zoom collar are from the rear and front sides respectively and there’s enough of them emerging for you to easily turn and push as required. The mode dial is sufficiently stuff that it won’t turn by accident.

The mode dial offers positions for Full Auto, Program, Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority, Manual, Memory Recall, Movie, HFR, Panorama and SCN – identical to the Mark IV and I’ll detail all of these later in the review.

The popup flash is housed in the middle of the body in-line with the optical axis of the lens. A small lever to the side and behind it releases the unit, and since the spring-loaded armature has flexible joints, it is possible (if not necessarily recommended) to use your left index finger to angle it slightly upwards for a mild bounce. In line with other compacts, the flash head itself is pretty small but it’s fine for close-range portraits in dim lighting; crank the sensitivity up to 6400 ISO and Sony reckons it’ll reach 10.2m at wide or 6.5m at telephoto, the distances differing due to the maximum lens aperture.

On the far left side of the upper surface you’ll find another panel, under which the electronic viewfinder is housed. A small switch on the left side of the body springs up the viewfinder, after which you’ll need to manually pull the eyepiece housing back towards you by about 5mm to activate it. This process powers-up the camera independently of the main on/off button, and pushing it back in and down again will power-off the camera by default, although like the RX100 IV you can configure the camera to stay powered-up when the viewfinder is pushed back into the body. When raised, eye detectors automatically switch between it and the main screen.

Like the Mark IV, the viewfinder panel sports a decent 2.3 Million dot / XGA / 1024×768 resolution with a magnification of 0.59x. This means it shares the same detail as the viewfinders even in high-end mirrorless cameras including Sony’s own A7 series, but with a lower magnification. As such the image you see in the viewfinder looks smaller than those on higher-end mirrorless cameras. I should also add the lack of an eye-cup means in bright conditions you may need to shield your eye from stray light with a finger from your left hand.

But to complain seems a little churlish when you remember Sony has still managed to squeeze a very usable viewfinder into a body no bigger than several rivals which do not offer the facility. Indeed I found myself using the viewfinder for almost every shot, and of course the extra point of contact with your face also improves stability.

Having a built-in viewfinder in this size of camera remains a key differentiator against much of the competition. In Canon’s current PowerShot G range, only the G5X sports an electronic viewfinder and while it’s also very good quality, it’s perched on top of the body in a DSLR-styled hump, making it immediately accessible but taller by almost 2cm. In contrast the RX100 IV’s body miraculously swallows its viewfinder entirely, making it more pocketable.

The only solution that’s more impressive still is the viewfinder housing on Sony’s considerably more expensive full-frame RX1R Mark II. Like the RX100 III, IV and V, its viewfinder pops-up from the top left corner of the body, but unlike those models the eyepiece housing mechanically extends back to you, eliminating the need to pull it back yourself as a second step. Impressively it’ll also fold back with a single push down, rather than the double-push currently required on the RX100 models. Sadly this mechanism hasn’t made it into the RX100 series yet, but to be fair the additional step on the Mark V requires only a minor effort and you find yourself subconsciously doing it when you see an opportunity approaching.

The RX100 Mark V is also of course equipped with a screen and it shares the same mechanism and panel as the Mark IV. So you get a 3in screen that tilts vertically down by around 45 degrees or up by 180 degrees to face the subject – handy for selfies or vlogging. The panel shares the same specification as the Mark IV with a 4:3 shape (meaning the wider 3:2 shaped images from the sensor are shown with shooting information underneath), and VGA / 640×480 pixel resolution. Both panels employ 1228k dots, which means four per pixel, the fourth being white. As a side-note, Canon and Panasonic also fits their PowerShot G and Lumix ranges with 3in screens, but they’re wider, matching the 3:2 shape of native images – so during composition and playback the images fill their screens and appear larger than the Sony’s, although shooting details have to be super-imposed as a result.

In terms of shooting information, the RX100 V lets you configure what’s displayed, including the choice of a graphical exposure scale, live histogram and a dual-axis leveling gauge; as before you can configure the screen and viewfinder details separately, showing different amounts of information or guides as desired. It’s also possible to superimpose a choice of three alignment grids. So far so good, but Sony misses out on a trick offered by Canon’s G5X which in turn was nicked from Fujifilm’s XT series: on those models the shooting information turns to stay upright in the viewfinder when the camera’s turned on its side.

A more important difference between the Canon, Panasonic and Sony displays is both Canon and Panasonic offer touch-screens on their G and recent Lumix bodies whereas Sony still doesn’t on the RX100 series to date. The touch-screens on the Canons and Panasonics let you swipe through menus, tap options, pinch to zoom and best of all reposition the AF area with a simple tap, something I do regularly and find absolutely invaluable. It’s also immeasurably easier to tap out text with a touch-screen which makes entering Wifi and copyright details relatively pain-free. Meanwhile on the Sony RX100 V, the priciest of all the 1in sensor compacts, the absence of a touch-screen makes the entering of details and adjustment of many options unnecessarily laborious. Indeed when shooting side-by-side with the RX100 V and Lumix LX10 / LX15, I was struck by how much easier it was to control and adjust the Panasonic over the Sony – and while that’s great news for the LX10 / LX15, it’s really not-on for the RX100 V when it’s priced-high and aimed at demanding enthusiasts.

The absence of a touch-screen on the RX100 V remains my single biggest complaint, as it was with all its predecessors. I really hope Sony addresses this with future models as it currently drives me towards Canon or Panasonic for usability.

Alongside the screen you’ll find exactly the same controls as the RX100 Mark IV. As such the action is concentrated around the tilting thumb wheel which provides just the right degree of resistance as it turns, avoiding any accidental presses. By default the four positions are configured – and labelled – for drive mode, display view, flash mode and exposure compensation, but the left, right and centre are reconfigurable in the menus from a choice of 45 functions. The wheel itself can also be customised, and below right you’ll find a dedicated custom button, with up to 49 options. Annoyingly out of almost 50 custom options, there’s still no way to configure a button to enter Flexible Spot mode with a single press, in turn allowing you to reposition the AF area with a minimum of button presses – you still need to choose it via the AF area menu, whether from a custom button or the menus. Again a touch-screen could have made this so much easier. McFly? McFly?

As before there’s also a ring control around the lens barrel, which by default offers context-sensible operation based on the shooting mode – for example controlling the aperture or shutter in aperture and shutter priority modes respectively. This too is customisable, allowing you to set the ring to adjust, say, the ISO or the zoom length. The operation remains smooth and step-free which is okay (and preferably for operation during movie recording), but I’d have still preferred stepped operation as it provides tactile feedback on how many positions you’ve moved along. Best of all, how about the ring on the Canon G7X Mark II which can be set to be clicked or smooth?

Behind two small flaps on the right side of the camera you’ll find the RX100 V’s two physical ports: Micro HDMI (with clean output) and Micro USB, both employing standard sockets so you can use standard cables. Sadly there’s no microphone input, nor any means to connect one wirelessly or via USB. To be fair, none of the pocket-sized 1in compacts have microphone solutions either, but it doesn’t stop me wishing they did. These cameras are the preferred choice of vloggers and having a mic input of some description would allow a big upgrade in sound quality. The opportunity is there for someone to take the lead.

The USB port on the Mark V serves multiple duties: beyond getting images and movies out of the camera, it doubles-up as a port for the optional RM-VPR1 cabled remote control and a battery charging socket. Like its predecessor, the Mark V recharges its battery internally over a USB connection and Sony supplies an AC-USB adapter in the box, although you’ll almost certainly have others that will do the job.

Some people don’t like to charge batteries inside their cameras as it effectively ties them up, but the flipside is that you don’t need to carry around a proprietary charger nor find an AC outlet to power it either. With charging inside the camera, you always have the charger with you, and by powering the process with USB you’ll have many options available which don’t involve being tied to a wall. For example you could recharge the camera using a cigarette lighter adapter in your car, or exploit the USB ports fitted into many vehicles including coaches or planes. If you have a laptop, you could recharge the camera using one of your USB ports, or you could simply use an external USB battery to topup or completely recharge absolutely anywhere. And of course when you are near mains power, you’ll almost certainly have an AC-USB adapter from another device like a phone or tablet that you could use with the camera.

I use an Anker PowerCore battery rated at 10000mAh to topup my phone when I’m out for long periods, and I love that I can also use it to topup my USB-powered cameras too. If I’m running low on either device, I’ll often connect the Anker while I walk between locations or catch public transport, and by the time I reach my destination they’re both significantly replenished without ever having to find a mains socket. I’ve been doing this with my older RX100 II for the past three years and have never been caught out, nor ever needed a spare battery. That said, the battery in the RX100 series is removeable, so you can still buy a spare if you really want, and Sony also sells an optional external BC-TRX USB charging sleeve for it if you don’t want to charge it inside the camera.

Like its predecessor, the RX100 V can even shoot when connected to an external USB power source. Powering-up earlier models – or rivals – would temporarily ignore any connected power sources, but now you can use them to keep shooting with the Mark V when your battery is low – great for extended filming or timelapse shooting. This capability was one of the hidden upgrades in the Mark II Alpha A7 series and I’m very glad to see it here too; it’s a key advantage over rivals which can only charge over USB.

As for the battery itself, the RX100 V is powered by the same NP-BX1 which powered its predecessors, and Sony quotes a life of around 220 shots per charge, down from the 280 quoted for the Mark IV and the 320 shots of the Mark III which itself was lower than the Mark II before it. Are Sony’s cameras becoming hungrier or are the testing conditions becoming stricter or more honest? Maybe the sensor with the embedded PDAF and or the front-side LSI are to blame? The bottom line is you have a small battery in a camera that’s packed with hungry features from 4k video to Wifi and they all take their toll. In general use while filming and using Wifi to share images, I got nowhere near the quoted life, but again since I always had a USB power source handy, I never got caught out. If you are out shooting all day or exploiting video and Wifi, I would advise either carrying a spare battery or having access to a topup over USB.

As before the SD memory card slot is housed in the battery compartment, and it’s also able to accommodate Sony’s own Memory Stick Duo cards. There is one important gotcha for those who wish to exploit the higher bit rates of the 4k or XAVC S 1080p movie modes though: you’ll need an SDXC card, which in turn normally means needing a card with at least a 64GB capacity. If you use non-SDXC cards, you’ll be limited to 1080p in AVCHD.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V lens

The Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V is equipped with the same lens as its predecessor: a 2.9x optical zoom with an equivalent range of 24-70mm and a bright focal ratio of f1.8-2.8. The closest closest focusing distance is 5cm at the wide-end and 30cm at the telephoto end. It’s a short but useful range, especially the ability to capture wide fields at 24mm equivalent. Here’s how it looks in practice.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V photo coverage, left at 24mm equiv, right at 70mm equiv

Looking at the competition, Canon’s PowerShot G7X II enjoys a longer optical range without compromising the focal ratio, with a 4.2x zoom equivalent to 24-100mm and an aperture of f1.8-2.8. Its closest focusing distance is also 5cm at wide angle, but 40cm when zoomed to the admittedly longer telephoto end. Meanwhile Panasonic’s Lumix LX10 / LX15 has a 24-72mm range with an f1.4-2.8 focal ratio and a closest focusing distance of 3cm at wide or 30cm at telephoto.

If you want longer telephoto reach from a 1in compact though, the Lumix TZ100 / ZS100 remains the current leader with a 10x / 25-250mm equivalent range, f2.8-5.9 focal ratio, and a closest focusing distance of 5cm when wide and 70cm at the long-end. So while all the models discussed here start at roughly the same wide-angle coverage of approximately 24mm, the Lumix TZ100 / ZS100 zooms two and a half times further than the G7X II and almost four times longer than the LX10 / LX15 and the Sony’s at the long-end, giving it considerably greater reach. The compromise is the focal ratio, with the TZ100 / ZS100 being roughly one stop dimmer throughout the same focal range as the shorter zoom models. This allows the Canon, Sony’s and LX10 / LX15 to deploy sensitivities one stop lower or shutter speeds twice as fast under the same conditions, and also achieve slightly shallower depth of field effects in the standard ranges.

So all these models enjoy compelling advantages over the Sony lens that’s now on its third generation: the G7X Mark II zooms almost 50% longer which not only gets you closer to distant subjects, but delivers more flattering perspective for portraits. The Lumix TZ100 / ZS100 zooms further still – four times longer than the Sony, albeit traded for a dimmer lens. Meanwhile the Lumix LX10 / LX15 has a brighter focal ratio and a closer focusing distance at the wide end, which will be welcomed by macro photographers.

A quick note on whereabouts in the range the apertures change. On the Sony RX100 III, IV and V the f1.8 aperture is only available at 24mm, slowing to f2 at 25mm and f2.5 at 28mm. Then at 32mm the lens slows to f2.8 and stays there for the rest of the range up to 70mm. The Canon G7X II starts at f1.8 at 24mm then slows to f2 at 28mm, f2.2 at 35mm, f2.5 at 39mm, then reaches its minimum aperture of f2.8 at 55mm and stays with it all the way up to 100mm. Meanwhile the LX10 / LX15’s enviable f1.4 aperture is only available at 24 or 25mm. It drops to f1.8 just 2mm into the range at 26mm, and to f2 at 26.5mm, before reaching its slowest f2.8 from 31mm onwards. So that two-thirds of a stop advantage is pretty much only when shooting at the widest angle.

So what differences in depth-of-field and rendering can you actually expect in practice? I’ll start with a portrait shot with the Sony and Canon at their maximum focal lengths and apertures, adjusting my position to maintain approximately the same subject framing. These images originally came from my RX100 III review which shares exactly the same lens as the Mark IV and V.

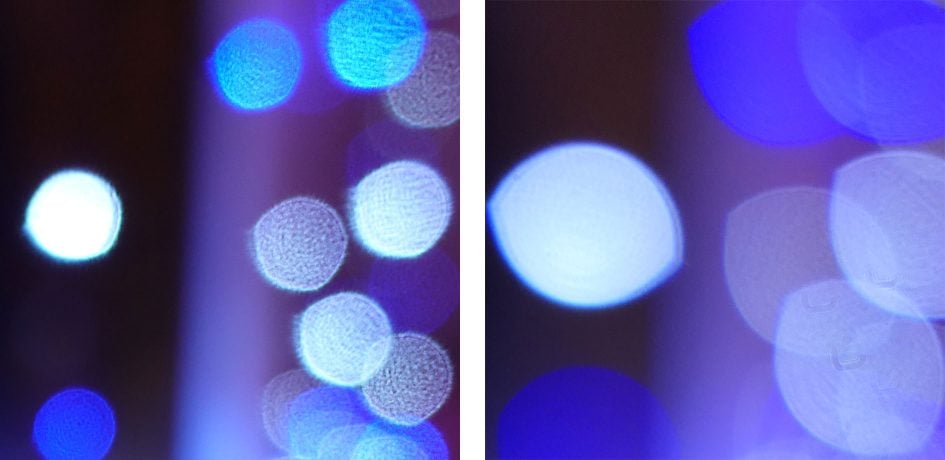

Above: Portrait bokeh: Canon G7X II (left) at 100mm f2.8, Sony RX100 III (right) at 70mm f2.8

The longer focal length of the G7X II has made the background elements bigger on the frame, including of course the defocused ones. So the blurring effect looks greater on the G7X II above left, than the RX100 V.

To really maximize the shallow depth of field effect you should get as close as possible to your subject, so I made a second comparison, this time against the Lumix LX10 / LX15, with both shooting at 24mm and their maximum apertures, and both at the Sony’s minimum focusing distance of 5cm.

Above: macro bokeh from 5cm distance: Sony RX100 V (left) at 24mm f1.8, Lumix LX10 / LX15 (right) at 24mm f1.4

As you can see above, the Lumix LX10 / LX15 optics render out-of-focus point sources of light as squashed cat’s-eyes, versus the more circular rendering of the Sony lens. Technically speaking, circles are optically more accurate, but many people prefer the look of the cat’s eyes. You may also notice concentric ‘onion rings’ on the Sony blobs, versus a more uniform fill on the Lumix, and the brighter aperture of the Lumix has also delivered larger blobs. For me the Lumix LX10 / LX15 looks better in this comparison, but wait, I have another comparison. As you may recall, the Lumix LX10 / LX15 not only has a brighter f1.4 focal ratio at 24mm, but it will also focus closer at 3cm versus 5cm. So here’s an additional comparison taken from each camera’s closest focusing distance, which on the LX10 / LX15 has allowed even greater blurring.

Above: macro bokeh from closest distance: Sony RX100 V (left) at 24mm f1.8, Lumix LX10 / LX15 (right) at 24mm f1.4

Above: Crops from images above: Sony RX100 V (left), Lumix LX10 / LX15 (right)

So the Canon G7X II is preferable for portraits (so long as you’re shooting at the telephoto end) and the Lumix LX10 / LX15 is preferable for macro shots (so long as you’re shooting at the wide end). And of course if you want a really long lens for getting closer to distant subjects, the Lumix TZ100 / ZS100 is the 1in camera for you. This leaves the Sony RX100 III, IV and V with the least exciting lens of its peer group. It’s a fine general range, but unlike the others it doesn’t take the lead in any respect. I think after deploying it on three generations of RX100 bodies, Sony should consider a new design for the next version to give it an edge against the competition in terms of optics. That said, the embedded phase-detect AF system gives the RX100 V a unique advantage over all these models when it comes to continuous AF and the burst shooting and slow motion video is unparalleled. So there’s lots to weigh-up and I’ll be discussing these other aspects in detail later in the review.

Moving on, the RX100 V inherits the built-in ND filter of the Mark III and IV which reduces the amount of light by three stops. This is useful for deploying large apertures in daylight conditions whether you’re shooting stills or filming video; it’s especially useful for video as you’re normally using fairly slow shutter speeds which should be no faster than double your frame rate for the best-looking motion. ND filters also let you extend exposures in dimmer conditions to deliberately blur motion, such as clouds or water during dawn or dusk. On the RX100 V you can set the ND filter to be on, off or set to Auto for stills, but for video it’s either on or off.

The Canon G7X Mark II also features a built-in three-stop ND filter, but annoyingly the Lumix LX10 / LX15 does not, which is a shame considering the high quality video available on that model.

Finally for this lens section I tested the optical image stabilisation by shooting a still-life subject at progressively slower shutter speeds first without stabilisation, then with it enabled. I used the RX100 V at its longest focal length of 70mm equivalent which, in traditional terms, would require a shutter speed of at least 1/70 to avoid shake when handholding.

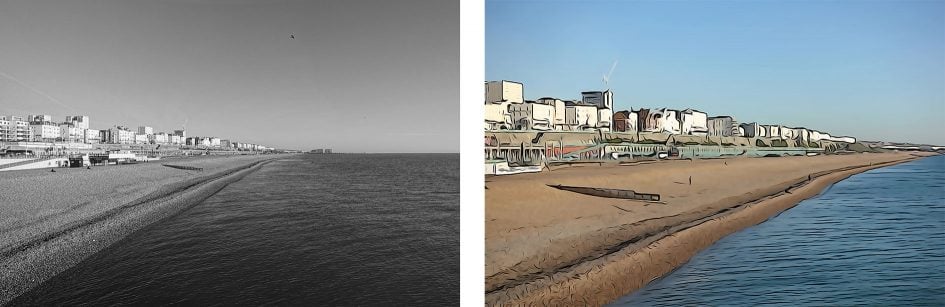

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V SteadyShot stabilisation at 70mm, 1/5: off (left), enabled (right)

On the day, I required a shutter of 1/80 to deliver shake-free images at 70mm without stabilisation, and managed to match the result at 1/10 with SteadyShot enabled, working out at a fairly standard three stops of compensation. The results at 1/5 were also quite good and acceptable when viewed at less than 100%. I’ve included the results at 1/5 without and with stabilisation above.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 Mark V shooting modes

The Cyber-shot RX100 V’s mode dial offers the usual PASM modes, Auto, SCN, Sweep Panorama, Movie, Memory Recall and HFR, for the High Frame Rate modes. As before, you can start filming video in any relevant mode by simply pressing the red record button, but by first putting the camera into the Movie mode, it’ll preview the composition frame and unlock more control.

The RX100 V’s mechanical shutter offers the same exposure range as its predecessor: 1/2000 to 30 seconds plus Bulb. The Mark V also inherits the electronic shutter option introduced on the Mark IV. This is not only completely silent, but offers shutter speeds up to 1/32000, giving the Mark V four additional stops of exposure control over the mechanical shutter. Since the Mark V also features a built-in 3-stop ND filter, you’ll be able to shoot with the aperture wide-open under extremely bright conditions if desired.

Electronic shutters may allow silent shooting and ultra-high speeds, but traditionally they’ve suffered from some issues: most notably potential for skewing of the subject or background if either are in sufficient motion during the sensor readout. Sony’s working hard to alleviate this though and quotes the RX100 V’s new sensor as having an Anti Distortion Shutter.

To put this to the test I shot a variety of straight vertical subjects using a panning motion which, with an electronic shutter, would normally result in the line leaning to one side. I also panned to follow fast subjects as they went past.

Like the Mark IV before it, the results were varied. In some comparisons there was no skewing what-so-ever, with the electronic shutter matching the output from the mechanical shutter. But occasionally I’d seem to trip the camera up and have a vertical line leaning on the electronic shutter version, but not with the mechanical one. The bottom line is while the RX100 V doesn’t appear to be totally immune to skewing with its electronic shutter, it’s certainly a great deal better than most cameras I’ve tested.

The ISO sensitivity can be set manually between 125 and 12800 ISO, extendable at the low-end to 80 and 100 ISO, or up to 25600 ISO at the high-end with Multi-frame Noise Reduction. There’s also a highly configurable Auto ISO mode which lets you set a minimum shutter speed from the full range between 30 seconds and 1/32000, or you can let the camera decide based on focal length. Like the higher-end Sony mirrorless cameras, you can also tweak the focal-length-aware option, encouraging the Mark V to deploy slower or faster shutter speeds than the usual one-over-focal length rule suggests. This can be useful if you desire slower speeds than the camera’s suggesting (perhaps to deliberately blur motion or because you’re very steady), or if you desire faster ones to freeze action. I found the Slow and Slower options generally selected shutter speeds one or two stops slower than the Standard setting, while Fast and Faster selected shutter speeds one or two stops faster.

Auto Exposure Bracketing is available on the RX100 V for three, five or an impressive nine frames at 0.3, 0.7, 1EV increments, or for three or five frames in 2 or 3EV increments. The availability of nine frame bracketing is an impressive addition to a compact.

As before you can set the drive mode for bracketing to Single or Continuous, and like the Mark IV there’s no need to hold the shutter release down to capture the entire burst. Instead simply choose Continuous Bracketing along with the ‘Self Timer during Bracket’ option within the Bracket Settings in the main menu; this lets you choose a self-timer of 2, 5 or 10 seconds after which the camera will capture the entire bracketed burst without further interaction. As before you can also set the bracket order, which is handy when organising bursts from, say, darkest to brightest. White Balance and DRO bracketing is also available.

While the option of a self timer just for brackets is a welcome one, I’m still dismayed by Sony’s general menu strategy, particularly how many options are greyed-out if an incompatible setting has been enabled. For example, like earlier Sony cameras, the RX100 V’s picture effects are greyed-out if you’re shooting RAW or RAW+JPEG, which is daft as it’d be nice to only have the effect applied to a JPEG and keep a RAW as backup. Olympus handles this much more sensibly with its ART filters, which are only applied to JPEG files, leaving the RAW file (if enabled) as a backup, and even lets you grab all (or a selected bunch) of the ART filters in one go with ART filter bracketing.

Anyway, back to the RX100 V. With RAW disabled, you can choose from Toy Camera (with five different filters), Pop Colour, Posterisation (in Colour or Black and White), Retro, Soft High Key, Partial Colour (with the choice of red, green, blue and yellow), High Contrast Mono, Soft focus (with the choice of Low, Mid or High), HDR Painting (with the choice of Low, Mid or High, or as I like to call them, awful, horrendous or appalling), Rich Tone Mono, Miniature (with the stripe of focus variable between Auto, Top, Middle Horizontal, Bottom, Right, Middle Vertical or Left), Watercolour, or Illustration (with the choice of Low, Mid or High). Here’s how a bunch of them look given the same real-life subject; note there’s still no way to apply a miniature effect on movies which is odd since most other cameras allow it and Sony is rarely caught out by such things.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Picture effects

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Picture effects

The D-R menu is where you’ll find the Dynamic Range Optimiser (DRO) and in-camera HDR options, the former available in Auto or set Levels of one to five, and the latter available as Auto or in increments of one to six EV. The HDR mode takes three images at the desired interval and combines them in-camera into a single JPEG file. If you have RAW or RAW+JPEG selected, the HDR options are greyed-out -thanks Sony. In the example below I used it to capture the bright background through the window without severely under-exposing the interior.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V HDR: disabled (left), 3EV enabled (right)

The SCN mode on the dial lets you choose from 13 presets, including the usual suspects like Portrait, Landscape and Sunset, but also including the composite Handheld Twilight and Anti Motion Blur modes which take a burst and combine them to reduce shake and noise.

The Sweep Panorama mode still enjoys its own dedicated position on the mode dial, and selecting it unlocks two options on the first menu page (although why Sony doesn’t let you set things in advance while you’re in other modes remains beyond me). Like previous Sony cameras you can choose between Standard and Wide for the size, and Right, Left, Up or Down for the direction. After that it’s just a case of holding the shutter release button down as you pan the camera in the selected direction, sometimes being told to do it again in case you were too slow or fast. Note you’re not allowed to adjust the optical zoom in the panorama mode – it sets itself to wide automatically and stays there.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Panorama: wide

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Panorama: tall

Sony was one of the first companies to deploy in-camera Panoramas and it remains a highlight of their cameras. It equally illustrates a key difference between them and Canon’s PowerShots which continue to not offer the facility. Even after several generations of development though, you should take Panoramas with relative care on the Sony cameras – you have to get the panning speed just right and it’s also worth taking a few backups in case, upon closer examination, the stitching on one isn’t quite as convincing as you’d hoped. I also found some of my panoramas included a small blank grey area on the far side, but this was easy to crop off.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V focus and continuous shooting

So far the RX100 Mark V has been essentially the same as its predecessor, but things get very different when we move onto autofocus and continuous shooting. In the first major upgrade, the RX100 Mark V becomes the first in the series to feature an array of embedded phase-detect autofocus points on the sensor – no fewer than 315 of them spread over 65% of the surface area. Phase-detect AF systems are generally more confident than contrast-based AF systems when it comes to knowing which way to focus and when to stop – so the hunting back and forth you see on contrast systems should be reduced or even eliminated, and continuous tracking should be improved.

The second major upgrade regards the burst speed and depth. The RX100 Mark V can shoot at 10fps with its mechanical shutter or at 24fps with its electronic shutter, both with continuous autofocus and exposure. Compare that to the Mark IV which shot at 16fps with the focus and exposure locked, or at 5.5fps with AF and auto exposure. Thanks to the presence of Sony’s new front-side LSI (Large Scale Integrated circuit), the Mark V can also burn-through processing duties, greatly extending the effective burst depth. Previously on the Mark IV I could shoot around 50 JPEGs at the top 16fps speed before it began to slow, although again with exposure and focus locked. Now Sony claims 150 JPEGs at 24fps, again with autofocus and exposure – I’ll tell you how it performs in practice in just a moment.

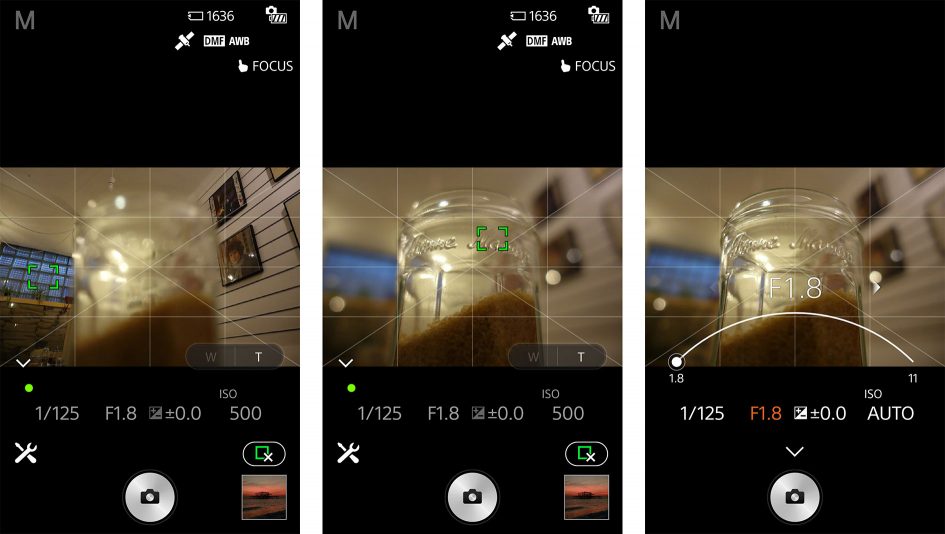

There may be a new AF system behind the scenes, but in terms of options, it looks a lot like its predecessor. There’s five modes for stills: AF-S (Single), AF-C (Continuous), AF-A (which automatically switches between Single and Continuous), DMF (Direct Manual Focus) and MF (Manual Focus). The choice of Single or Continuous has no effect in the movie mode where it’s still either Continuous AF or Manual focus only. Note DMF lets you autofocus with a half-press of the shutter release, after which you can fine tune manually by turning the lens barrel ring. Focus peaking is also available for DMF and MF modes, which helps you nail the focus by outlining the edges of sharp subjects. If MF Assist is enabled in the menus, the view is temporarily enlarged, allowing you to take a closer look as you turn the wheel.

The RX100 V also inherits its predecessor’s AF area options, allowing you to choose from Wide (which chooses for you across the entire array), Center, Flexible Spot (which lets you manually position a single AF point of three sizes) or Expand Flexible Spot (which works like Flexible Spot set to the Small size, but also considers a small area around it). Unlike the Alpha range there’s still no Zoning options.

If AF-C is enabled, you can also choose Lock-on AF which tracks a subject based on its shape and colour, surrounding it with an elastic frame that changes shape and size depending on where it is in relation to the camera. Lock-on AF is available with Wide, Center, Flexible Spot (small, medium or large), or Expand Flexible Spot. To kick-off you position the active AF area over the subject (or in the case of Wide, hope that it’s automatically identified), then simply keep the shutter half-pressed for the camera to subsequently track it.

If Face Detection is enabled, it’ll over-ride any of the area options if a human face is detected. If you’ve pre-registered specific faces with the camera, it’ll also give them priority over others – handy at an event like a wedding where you can prioritise the Bride and Groom in a group shot. There’s also optional Eye Detection which now works with the new phase-detect AF system in AF-C mode.

Ah yes, the embedded phase-detect AF system – so how well does it work in practice? In Single AF / AF-S modes, the RX100 V unsurprisingly executes the autofocus operation like its bigger Alpha siblings which also sport hybrid systems. As such it first employs the phase-detect system to get close to the point of focus, then finishes the job with a contrast-based feedback loop – as such there’s a small amount of hunting back and forth at the end of the process but it all takes place pretty swiftly. In use it felt similar to rival 1in compacts in speed but occasionally faster. If you have pre-focusing enabled, the subject is also invariably sharp or close to sharpness as you compose the shot, so that when you finally press the shutter release, there’s not much work to do. Note if you manually position the AF area as far to the sides as possible, it’ll be just outside the region of phase-detect coverage and become 100% contrast-based.

Set to Continuous autofocus / AF-C, the RX100 V exclusively uses its phase-detect AF system, which in turn means it’ll only work within the area of coverage. The phase-detect area may ‘only’ cover 65% of the sensor, but in practice this only excludes a minor border around the extreme edges, so in use, you’re very unlikely to have a subject entirely within these neglected strips.

Depending on the AF area mode, you’ll see a scattering of tiny squares representing the active phase-detect points positioned over the subject – or what the camera believes is the subject – and it’s fascinating to watch them buzz around like a swarm of tiny green-square bees. If you’ve chosen Flexible or Expand Flexible Spot, the AF system stays where you told it to, but in Wide or the Lock-On modes, you’ll see the entire array kick-in.

Like the Alpha cameras with embedded PDAF, the results can be impressive but you will need to spend some time learning which modes work best for various conditions. And like all focal plane phase-detect systems I’ve tested so far, much of the trick is to ensure the subject is sufficiently large on the frame for you to positively identify it to the AF system.

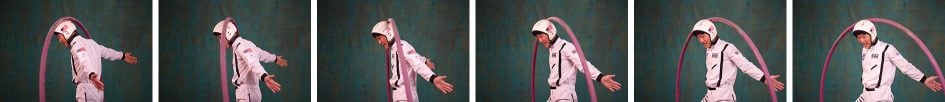

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous AF / Wide Area / 24fps

When the subject would quickly appear in the frame, I found the Wide area did a good job at not just identifying them, but also focusing very quickly on them – this is an ideal choice for unpredictable kids, pets, birds or close-range sports like tennis or basketball from the sidelines. When the subject is more predictable you can deploy the smaller (Expand) Flexible Spot options, drilling-down on the areas covered. These are better for avoiding distracting backgrounds, but like most AF systems will prioritise whatever’s closest in the area under consideration. So if there’s road in front of a cyclist, splashes in front of a wakeboarder or sand being kicked-up from a horse, these may persuade the AF system to focus in front of the desired subject. The answer then is to choose the smaller areas, and again to wait until the desired subject is big enough for the AF system to absolutely know this is what you want to track.

Get it right and the RX100 V can refocus on moving subjects with a fairly high degree of keepers. Here’s a sequence of my friend Ben cycling directly towards me. We tried multiple passes comparing Flexible Spot, Expand Flexible Spot and Lock-on versions of both, and found the first two most effective – but again only when he was close enough for me to fill the AF area with the desired portion, such as his face or torso. Here’s a sequence of 24 images, with a cropped portion under each.

Below: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous AF using Expand Flexible Spot (full image followed by 100% crop)

In my tests with approaching cyclists the RX100 V’s continuous AF may not have been as decisive as I’d hoped, and it certainly wasn’t like having a pocket-sized Alpha A6300 / A6500 in terms of confidence and consistency. It’s also worth remembering the depth-of-field is fairly large and forgiving on cameras like these, so the challenge of keeping the subject sharp isn’t as hard as on a larger sensor camera with an often brighter lens. But the bottom line is in most situations the RX100V’s continuous AF still proved more effective than rival 1in compacts I’ve tested which rely on contrast-based AF systems alone.

But the RX100 V’s phase-detect AF can be used for more than just still photography – it can also be deployed during movie recording where, in my tests, it proved much more compelling. Now the RX100 V can decisively refocus between subjects when filming with minimal or no hunting back and forth, and while it cries out for a touch-screen, it’s still an upgrade over previous models – not to mention rivals which are contrast-based only. Again, to manage your expectations, it’s better with subjects moving at a fairly leisurely pace as opposed to racing towards you. Here’s two examples and I have more in the movie section later.

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

The AF system may have been upgraded, but manually positioning a single AF area is still harder than it should be. You first need to select Flexible Spot or Expand Flexible Spot from the AF area menu before the AF area itself becomes live and adjustable on-screen; you can assign AF Area to a custom button, but you still need to subsequently select (Expand) Flexible Spot before you can begin manually adjusting the AF area position.

I tested the RX100 V alongside Panasonic’s Lumix LX10 / LX15 and was struck how much easier this process was thanks to its touch-screen. Just tap wherever you’d like it to focus and bingo, job-done. I say it in every Sony camera review, but I really feel their usability could be improved considerably with a touch-screen. The company may have finally relented and equipped the Alpha A6500 with one, but the RX100 / RX10 series are still left wanting.

Going into continuous shooting in more detail, the RX100 V offers three burst speeds: Low and Mid shoot at 3.5 or 10fps and both employ a mechanical shutter, while High shoots at 24fps with an electronic shutter. What really separates the RX100 V from its predecessor and rivals though are auto exposure and autofocus are available at any of the burst speeds and you have the choice of recording full size JPEGs or RAW files. The bursts can be very deep too with Sony quoting 150 JPEGs captured, even at the top 24fps.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous AF / Flexible Spot / 24fps

This is seriously impressive stuff and possible thanks to the combination of the Stacked CMOS sensor introduced on the Mark IV (with its embedded DRAM and fast data readout) and the addition of Sony’s new front-side LSI (Large Scale Integrated circuit). The LSI speeds through image processing and its position in relation to the sensor means it’s never short of data to chew on. Sony’s already equipped the A6500 and A99 Mark II with the same LSI, so it looks like becoming a standard feature at least on the higher-end models.

Meanwhile 24fps is fast enough for almost any situation and as a video frame rate, also means your bursts could be used to create short movie clips at higher than 4k resolution. I’ve seen some examples which don’t look as convincing as videos filmed in the native movie modes, but it does point to an interesting convergence in the future.

Right, those are the numbers and the theory – now, how does the RX100 V perform in practice? To put it to the test I fitted a freshly-formatted UHS-I U3 / Class 10 SDXC card, set the shutter and sensitivity to 1/500 and 400 ISO, before timing a number of bursts.

With the quality set to Fine JPEG and using the mechanical shutter (the Mid speed setting), I fired-off 195 frames in 19.48 seconds before the camera began to stall; this corresponded to a speed of 9.86fps. Switching to the electronic shutter unlocked the Hi speed mode, allowing me to capture 160 frames in 6.47 seconds before slowing, for a rate of 24.7fps. Meanwhile it took about 30 seconds to clear 100 JPEGs from the buffer during which time you can playback images already recorded to the card (and see a countdown on how many still need to be written) or shoot a handful more images but not enter the menu system.

Setting the quality to RAW, I managed 73 frames in 7.32 seconds using the mechanical shutter / Mid speed, for a rate of 9.97fps. With the burst speed set to Hi with the electronic shutter, I managed 71 frames in 3.01 seconds before stuttering, for a speed of 23.6fps. When shooting RAW, it typically took 34 seconds to unload 50 RAW files from the buffer onto the card I was using.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous AF / Wide Area / 24fps

These all represent a significant improvement over the earlier Mark IV. On that model, I could shoot unlimited JPEGs at 5.67fps, or 50 at 15.3fps, before slowing. In RAW, the Mark IV let me capture 30 frames at 5.82fps or 28 at 8.92fps before both modes slowed a great deal.

So the RX100 Mark V can shoot twice as fast with its mechanical shutter or 50% faster with its electronic shutter than the Mark IV, and for much longer bursts too. Best of all, the electronic shutter is very usable with no perceptible rolling shutter in my tests (even with vigorous panning of the camera), and when you’re shooting at 24fps, the viewfinder is effectively showing you live feedback in the viewfinder with minimal blackout.

If you’ve shot action at 8, 10 or even 16fps, you may wonder if 24fps is slightly excessive and more a case of technical showing-off. But in many cases the subject can move significantly between frames even at this speed, so being able to capture 24fps for sustained bursts really gives the RX100 V an edge over its rivals for action photography. Here’s three examples showing 24 frames each, therefore representing just one second of action – it’s clear how there’s plenty of differences in these sequences.

Below: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous Shooting High at 24fps. Sequence represents one second of action

Below: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous Shooting High at 24fps. Sequence represents one second of action

Below: Sony RX100 Mark V Continuous Shooting High at 24fps. Sequence represents one second of action

The combination of fast and deep bursts with embedded phase-detect AF makes the RX100 Mark V by far the most desirable premium compact for action shooting, although the question remains if this is the kind of camera and lens you’d want for sports. It’s neither wide enough for ultra-close action, nor long enough to reach distant action, nor have a sufficiently shallow depth-of-field to isolate a subject against a busy background. You’ll need to decide for yourself if the sensor, lens and body are suitable for the kind of action you want to shoot, but certainly in terms of processing power, the Mark V is the most powerful premium compact to date.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V Wifi and NFC

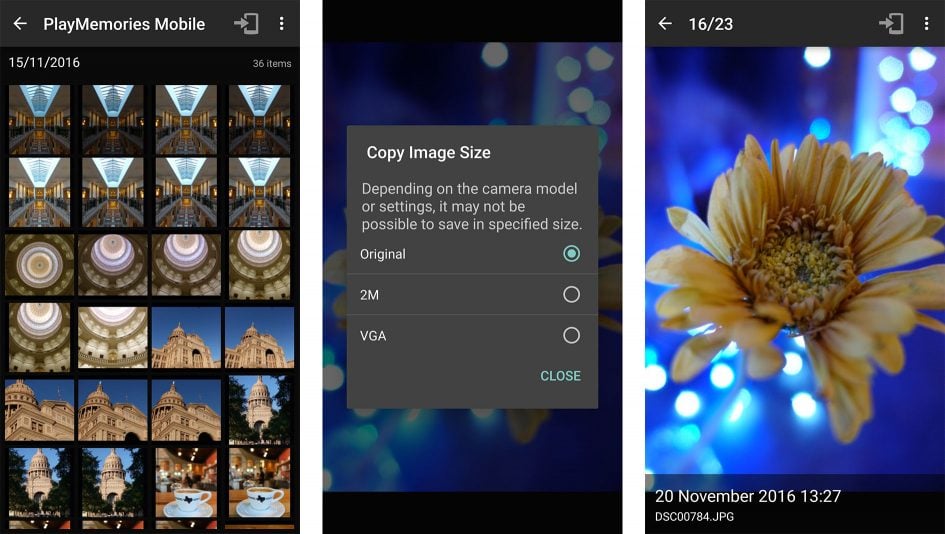

The Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V has built-in Wifi with NFC to aid negotiation with compatible devices. Wifi on the RX100 V allows you to wirelessly browse and transfer JPEG images onto an iOS or Android smartphone using a free app, and also remote control the camera with your phone or tablet. The RX100 V can additionally download apps directly to extend its capabilities, a feature first introduced on the NEX-6, and a capability that remains unique to Sony (if we’re not counting Android-powered cameras from the likes of Samsung or Panasonic).

I’ll start with transferring images from the RX100 V to a smartphone and for my tests I used my Samsung Galaxy S7, onto which I’d previously installed Sony’s free PlayMemories app. If you have an NFC-equipped device, such as my GS7, the entire process is incredibly simple: just choose the image you want in playback on the camera, then hold it against your phone. The NFC then instructs the camera and phone to connect (automatically taking care of network names and passwords), before then transferring the image and finally disconnecting. It all happens without a single button press and remains the best implementation I’ve seen for copying images from camera to phone.

If you don’t have NFC, or for some reason it doesn’t work, you’ll need to connect to the RX100 V’s Wifi network manually. First go to the Wireless section and choose the option to Send to Smartphone. This then gives you the choice of either selecting the desired image on the camera, or browsing the camera’s memory using your handset. Selecting either configures the RX100 V as a Wifi access point which your phone needs to connect to. Next you’ll need to fire-up the PlayMemories app on your phone and connect to the camera.

If you opt to select the image on the camera, it’ll then be sent straight to the phone. If you select the option to choose with your smartphone, you’ll see the camera’s images presented in a thumbnail view – just select the desired image and again it’ll be copied over. A menu in the PlayMemories app lets you choose whether the image is sent in its original 20 Megapixel format or resized down to VGA or 2 Megapixels. Full sized 20 Megapixel JPEGs take about five seconds to copy over; like most Wifi camera apps, you can’t transfer RAW files, and while you can playback non-AVCHD movie files, I couldn’t find a way to copy them onto my phone either.

Next I’ll cover remote control which requires the Smart Remote app to be installed on the camera – as luck would have it, Sony embeds this into the RX100 V to get you started in the World of apps, no doubt in an attempt to get you comfortable with the idea and possibly purchase some more in the future – although there is a catch I’ll mention in a moment.

Once again, Sony makes things really easy for owners of NFC phones. With the camera powered-up and ready to shoot, simply hold your phone against the NFC logo on the side of the body and the RX100 V will automatically fire-up the Smart Remote app, connect itself to your phone (again taking care of Wifi network names and passwords), then start the PlayMemories app. So without a single button press, you’ll find your self ready to remote-control the camera with your phone. Brilliant! If you don’t have a phone with NFC, you’ll need to first select the Smart Remote from the App menu on the RX100 V. This sets the camera up as an access point for the PlayMemories app on your phone to connect to.

Once you’re remote-controlling your camera, you’ll be able to see what it sees, adjust the exposure compensation and take a photo when desired. But out-of-the-box you won’t be able to change the aperture, shutter speed or ISO, nor reposition the AF area. There is however a solution: an update to the in-camera Smart Remote app unlocks full exposure control along with the chance to tap anywhere on your phone’s screen to move the AF area for still photos – some consolation for the absence of a touch-screen on the camera itself, although sadly it’s not allowed while filming videos.

To update the app, you’ll need to connect the RX100 V directly to the internet, log into the PlayMemories service (using an account you’ve previously set up on a computer), choose Smart Remote in the camera’s Application menu, then select the update option. Alternatively you can download an app via a browser on a laptop or desktop, then connect the RX100 V to transfer it.

A few seconds later you’ll have the latest version of Smart Remote sporting a wealth of manual control. It’s great the camera offers this, but a shame you need to go looking for it, as I’m sure many owners won’t jump through the required hoops. It’s the same situation with all Sony cameras to date and I personally hate having to update them, especially the laborious process of entering Wifi and PlayMemories passwords without a touchscreen. Sony really ought to ship its cameras with a fully-featured version of Smart Remote. It’s also a shame that while you can trigger a movie using Smart Remote, you can’t use the screen on your phone to reposition the AF area by touch, as you can when shooting stills.

While updating the Smart Remote, you’ll notice a selection of other apps you can download to extend the capabilities of the camera, some free, some costing up to $9.99. Arguably the most powerful app is Timelapse which has gradually become more sophisticated over several updates. It now works alongside a new Angle Shift Add-On ($4.99) that lets you perform pans, tilts and zooms within a timelapse video, all generated in-camera.

A Beta section in the download section also lets you access apps under development. I tried the Touchless Shutter app (still free in beta) which cleverly exploits the viewfinder eye sensor to trigger the shutter – simply wave your hand close to the viewfinder and the camera takes the shot. Better still, it also works in Bulb mode with a wave to start an exposure and another wave to end it.

There’s also apps to simulate the effect of long exposures by combining multiple frames and ones designed to better capture light or star trails. It’s all good fun, but the question is whether most or even all of these should just be part of the standard camera operating system. After all most rivals offer built-in timelapse facilities, and an increasing number offer Bulb timers or other innovative long exposure options.

I also find Sony’s apps aren’t always accessed or adjusted in an intuitive manner. Rather than integrating new functions into the existing menus, they’re all kept in a dedicated Apps section. I’m sorta okay with that, but once you fire-up an app, you’ll find it has its own multi-page menu system, including duplicate options for some settings, sometimes including image quality. Yep, a separate image quality menu just for that app that works independently of the main image quality menu for the camera. So you may have the main menu set to, say, RAW+JPEG, then enter an app assuming it’ll inherit that setting, only to discover later that you’ll need to set it separately. This caught me out a few times when using, say, the Touchless Shutter app. I assumed it would be capturing images using my main quality settings, but was in fact using a default setting of JPEG only. Why would I want to have different quality settings just because I’m using an app? I was also frustrated to find the ND filter option wasn’t available in the Touchless Shutter app menus, which is surely a desirable option when shooting Bulb. Sony really needs to think more carefully about how the Apps integrate with the camera. Just one menu please. In fact, how about dumping the app approach altogether and just integrating the features into the camera’s operating system and user interface?

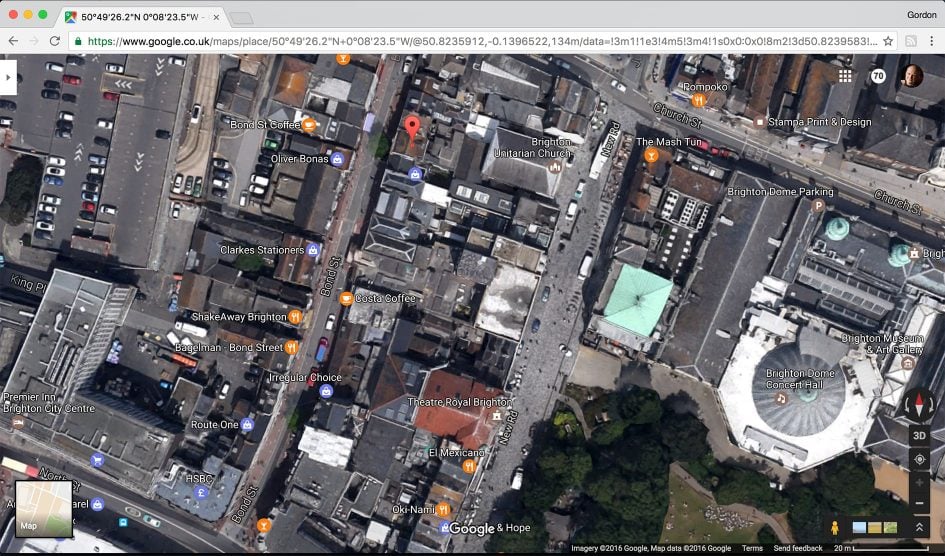

As you browse the Apps and experiment with Smart Remote, you’ll also notice a lack of GPS logging options. Most camera apps now offer an option to record a GPS log that’s then synced with your photos after a day’s shooting. To me that makes the most sense, but Sony has instead gone for an approach which only offers to embed a position when you take a photo using the Smart Remote. But wait, the location isn’t embedded in the file recorded by the camera. Instead it’s only embedded in the image copied onto your phone, which may not be at the full resolution. So unless you’ve ticked ‘Original’ as the ‘Size of Review Image’ setting in the Smartphone app (while the remote control is running), you could find yourself with a high-res image in the camera without a location and the same shot on your phone with the location, but at a lower resolution. Configure all the options carefully and your phone should store an original resolution file with the location embedded, which you could then copy back to a computer but it’s overly complicated. Sony, please just offer a GPS logging option in the Smart Remote app that syncs the location on a bunch of images in the camera, or better still, equip all your new cameras with the Bluetooth solution implemented on the Alpha A6500 which maintains a low-power link with your smartphone and sorts out the location embedding without intervention.

In order to capture the image below in the full resolution image with the location embedded, I first configured the Size of Review Image in the Play Memories app on my phone to Original and then ticked Location logging. I then set the camera to shoot, held my phone against it to trigger the Smart Remote control, checked that the satellite icon was visible in the corner of the phone’s screen, then took the photo. I then copied the image into Dropbox to sync it with my computer, and after that entered the GPS co-ordinates into Google maps for the map view. Phew. Easy, right?

Below: Sony RX100 Mark V photo tagged with GPS position with co-ordinates entered into map

But it seems slightly churlish to complain when the most common processes of wireless image transfer and remote control continue to work so well here, at least when the in-camera app has been updated. If Sony ships its future cameras with Bluetooth for easy GPS tagging and a fully-featured version of Smart Remote (or just integrates it into the OS), then I’ll be very happy.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V High Frame Rate movies

High Frame Rate video, or HFR for short, was introduced on the previous RX100 Mark IV. Thanks to the stacked sensor with embedded DRAM, it could capture and process data at enormously fast rates, allowing video capture at 240, 480 and even 960fps. The only limitation was the capture period of two or four seconds depending on the mode. When slowed by as much as 40x, two or four seconds still results in a lot of footage, but it could still be a challenge to capture the decisive moment.

The RX100 Mark V inherits the same HFR modes, but thanks to the addition of the front-side LSI chip can now process the data faster than before – in turn allowing longer capture periods.

When the mode dial is set to the dedicated HFR position, the camera can capture video at a choice of three very high frame rates: 240 / 250fps, 480 / 500fps or 960 / 1000fps in NTSC / PAL regions respectively. These are automatically conformed in-camera to (your choice of) either 25p or 50p for PAL regions, or 24p, 30p or 60p for NTSC regions. If you choose the 25p and 24p options, the three recording modes will slow-down the action by 10, 20 or 40 times respectively.

There are understandably a number of restrictions when filming at these sort of speeds. First is the recording time with two options: Shoot Time Priority mode captures eight seconds of action, while Quality Priority captures four seconds. That doesn’t sound like much, but both modes are now recording for twice the length of time as on the Mark IV. This in particular makes the Quality priority mode much more usable than before, as four seconds allows you to much more easily capture the best moments, whereas two seconds could be quite tight in practice.

You also wouldn’t want to record for much longer as the clips take a while to record onto your card after capturing; indeed the RX100 V records them in real-time, so if the final clip will last, say, 40 seconds, it’ll take that long to save it to the card.

I did some timings and found the maximum recording time at 240fps using Quality Priority conformed to 24fps resulted in a 47 second clip which took the same 47 seconds to record to the card. Meanwhile switching to 960fps, again for the longest recording time in Quality Priority and conformed to 24fps resulted in a 2 minute 40 second file which again took 2 minutes and 40 seconds to record. Remember this is using the Quality Priority mode; if you selected Shoot Time Priority, you’d have to wait potentially twice as long.

During the recording process the camera previews the footage in conformed slow-motion, and allows you to abort the recording if it’s clearly not what you had in mind, but there’s no option to stop mid-way and just record that part. I realise there may be some fiercely complex buffering going on, but it’s a shame not to be able to interrupt a recording when you’ve discovered the bit you want is at the start. Instead you have to wait patiently for the entire clip to finish recording which, as noted above, could be several minutes.

The second limitation is the quality which reduces as the frame rate increases. Set the camera to Shoot Time Priority, and the 240 / 250fps mode will capture video at 1676×566 pixels, while the 480 / 500fps and 960 / 1000fps modes record at 1136×384 and 800×270 pixels respectively. Set the camera to Quality Priority and the 240 / 250fps mode will capture video at 1824×1026 pixels, while the 480 / 500fps and 960 / 1000fps modes record at 1676×566 and 1136×384 pixels respectively. In every case, the video is up-scaled to 1080p resolution and the 16:9 shape so it’s ready to slot-into in a standard 1080 timeline.

That’s a lot of numbers to digest, but when set to 240 / 250fps, the Quality Priority mode is only just shy of delivering Full HD / 1080p resolution, while the 480 / 500fps mode is close to HD / 720p quality. This means you can enjoy close to HD quality with a 10x or 20x slow-down, and if you’re happy with standard definition quality, you can slow footage by 40x.

Sony’s also had a good think about how best to capture bursts that only last up to four or eight seconds. By default the HFR modes start recording when you press the record button and stop two or four seconds later, but an alternative End Trigger option constantly buffers the video and stores the previous four or eight seconds when you press the button. The idea is to follow the action as it happens, then once the decisive moment has completed, such as landing a jump or hitting a target, you press the button and the camera stores the last four or eight seconds depending on the quality mode. The constant buffering employed by the End Trigger mode chews through your battery quickly but allows you more easily capture the exact moment of action and end up with more successful footage.

There’s one other thing to mention: before HFR capture can take place, the RX100 V needs to prepare itself. So the first step is to press the centre of the rear wheel, wait for a couple of seconds, then when the camera reports ‘Standby’, it’s ready to start the capture with a press of the movie record button.

That’s enough background, now let’s see how the modes look in practice. I’ve put together a compilation of clips filmed with the RX100 V’s three HFR Quality Priority modes, along with its 1080 / 120p mode which allows a 4x slow-down in Full HD quality. As noted above all the clips are upscaled by the camera to 1080p, so they slot right into a 1080 timeline without scaling, although again the quality reduces as the frame rate increases. The quality may be unchanged from the Mark IV, but the ability to record clips twice as long as before certainly makes it much easier to capture the decisive moment, especially in the Quality Priority mode.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V movie mode

The RX100 Mark V is a very capable camera for filming video, inheriting the quality and control of the Mark IV, but now with the added benefit of a phase-detect AF system for smoother and more confident refocusing. Highlights include 4k recording up to 30p, 1080 recording up to 120p and the High Frame Rate modes described in the previous section which allow 10x, 20x and even 40x slowdowns.

When filming in 4k, the RX100 V takes a mild crop (approximately 1.1x horizontally) and lets you record at 25p in PAL or 24p / 30p for NTSC and at a choice of 60 or 100Mbit/s; as before the longest recording time in 4k is five minutes per clip to avoid over-heating, although you’re welcome to start another recording straightaway afterwards if desired. I managed to record three clips lasting five minutes each before the temperature icon appeared, and one more before the camera warned the temperature was too high and shut itself down. The Mark V felt warm, but not hot at this point and after a few minutes of cooldown was happy to record two more five minute clips again. But from this point onwards it would shut itself down after a decreasing period: first after a couple of minutes, then gradually as little as 30 seconds. I kept going until the battery gave up, at which point I’d recorded just under an hour’s worth of 4k footage in total, but with so many short clips by the end of the process, I only realistically enjoyed about half an hour’s worth of usable five minute clips.

Note the Lumix LX10 / LX15 is a similarly-sized compact with a 1in sensor and support for 4k video, but it takes the lead over the RX100 V with longer 15 minute 4k clips; I managed 77 minute’s worth on a single charge with five consecutive 15 minute clips and one lasting a couple of minutes at the end without any overheating, although it does apply a more severe 1.5x crop when filming 4k.

If you’re filming 1080p there’s a wealth of options on the RX100 V. With the camera set to XAVC S, you can record 1080 at 25p / 50p in PAL regions, or 24p / 30p / 60p in NTSC regions, all at 50Mbit/s. You can also film at 100 / 120p for PAL / NTSC at 60 or 100Mbit/s, allowing a 4x slowdown, or 5x if you’re using the 120p on a 24p timeline. It’s possible to switch the camera between PAL and NTSC to access all the frame rates, although doing so will require a reformat of the card so if you’re likely to switch frame rates regularly, you should carry a card for PAL and a card for NTSC. Like all Sony cameras, you’ll also need an SDXC card (64GB or higher) to support the XAVC S and 4k modes.

If you want to squeeze more footage onto your card, there’s lower bit rate AVCHD options available, offering 1080 at 50p / 60p at 28Mbit/s, 50i / 60i at 24 or 17Mbit/s, or 25p / 24p again at 24 or 17Mbit/s. Finally, the MP4 menu unlocks 1080p at 50p / 60p at 28Mbit/s, 25p / 30p at 16Mbit/s or 720p at 25 / 30p at 6Mbit/s. Whether filming 1080p in XAVC S or AVCHD, the longest single clip I could capture lasted just a few seconds shy of 30 minutes; my RX100 V sample came from the US, so this wasn’t a European restriction.

Like its predecessor, the RX100 V’s sensor readout is sufficiently quick for it to capture 17 Megapixel / 16:9 still photos while it’s filming, albeit with some caveats. On my sample camera fitted with a UHS-I U3 / Class 10 SDXC card (94MB/s), I could capture stills while recording movies in any quality so long as the movie bit rate didn’t exceed 50Mbit/s. This meant I was okay to capture 17 Megapixel stills while filming 1080 video, even at 50p or 60p in XAVCS (50Mbit/s), but sadly it was not possible when filming 4k video at 100 or 60Mbit/s. What leads me to think it’s a bit-rate limitation rather than a 4k limitation is I couldn’t capture photos while filming in 1080 / 100p / 120p which also run at 100 or 60Mbit/s.

If you want still photos and 4k footage, you’ll need to record in 4k, then extract stills afterwards, although these will of course be at the lower 4k frame resolution of about 8 Megapixels. With a 4k clip in playback, you can select Photo Capture from the playback menu before shuttling through the footage and extracting as many stills as you like. So in terms of photo quality the RX100 V is working a little like the 4k Photo modes on Lumix cameras, albeit with a less slick interface and fewer options, but I’d love to see Sony’s prowess in image processing speed allow the capture of 17 Megapixel stills while filming 4k video. I believe it’s something that may be possible with its professional movie cameras which makes me think it could be an SD card speed issue – perhaps we need proper support for UHS-II cards.

Moving on, the RX100 V offers full manual control over exposures with the choice of filming in Program, Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority or full Manual. You can adjust the aperture, shutter, ISO, exposure compensation and even the AF mode while filming. The rear wheel and front lens ring perform the adjustments of whatever two settings they’ve previously been assigned to, and while the rear wheel clicks, the lens ring is smooth and silent as you turn it – so ideally assign the lens ring to adjust the desired setting before you start filming.

The full sensitivity range is available for movies up to 12800 ISO and there’s an Auto ISO option that works in any of the exposure modes including Manual; it’s also possible to apply exposure compensation when shooting in Manual with Auto ISO, although you’ll either need to pre-assign it to a dial or access it via the Fn menu.

You can apply a selection of Creative Styles, which also provide manual tweaking of contrast, saturation and sharpness. You can also apply a selection of Picture Profiles which include S-Log 2 under profile 7 for fairly flat output that’s ready for subsequent grading. Note S-Log 3 is not available.

You can also enter the on-screen Fn menu while filming to highlight another setting to adjust, although doing so will inevitably wobble the camera and result in audible clicks, but if you can’t bear to stop the recording, it’s nice to have the option. Meanwhile, optional Zebra patterns from 70 to 100 in increments of five allow you to accurately judge the exposure on-screen. Speaking of the screen there’s no way to boost the brightness when filming in 4k (the Sunny Weather option is only available when shooting 1080p), but the standard brightness still seemed better to me than on the A6300 / A6500 and more usable outdoors. You can of course alternatively use the viewfinder.

As noted in the lens section, the RX100 V also features a built-in ND filter that soaks-up three stops of light. This is useful for deploying larger apertures in bright conditions without resorting to faster shutter speeds which aren’t optimal for motion. I frequently used the ND filter for achieving motion-friendly shutter speeds.

Like earlier Sony cameras, the focus menu still only offers AF-C continuous or MF manual options – sadly there’s still no AF-S single option, and worse there’s still no way to specify exactly where you’d like the camera to focus. So in AF-C mode, the camera focuses when and where it likes. Offering some consolation is Lock-On Area AF which lets you position a central target over the desired subject, after which the camera will follow it around the frame, refocusing if required. If Face Detection is enabled, the camera will also lock onto human faces and refocus on them too, as demonstrated in a clip in the focusing section earlier.

But I’d still like to set a specific area myself to define exactly where I’d like the camera to focus, and I’d like an AF-S option so that I can effectively tell the camera when to start refocusing and when to stay focused where it is. Luckily the new phase-detect AF system is pretty good at settling on a subject and not breathing to confirm, and as mentioned in the focusing section, it also allows the RX100 V to confidently refocus with minimal or zero hunting. Here’s another clip to demonstrate it.

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

If you want to control the focus precisely, you’ll need to switch to MF mode, although optional focus peaking does at least make it easier to judge which regions will be sharp. You can also assign manual focus to the lens ring, allowing smooth adjustments prior to filming and during too.

Right, now it’s time to see how the quality measures-up. First are screengrabs taken from 4k and 1080p footage with the lens set to the same focal length. This allows us to compare the coverage / crop factor. As stated earlier the RX100 V uses the full sensor width when filming 1080p, but applies a mild 1.1x crop when filming 4k. The outer edge of the red frame indicates the area of 4k coverage compared to 1080p at the same focal length.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V movie coverage: 1080p (24-60p) full image, 4k represented by outer edge of red frame

How about a quality comparison? I filmed a clip in 1080p with the lens roughly mid-way through its range, then for a level playing field adjusted the zoom to match the field of view in 4k. I’ve taken crops from each clip below and you can see the 4k version is capturing significantly more detail. 4k footage also downscales to 1080p very nicely and if you’re happy with frame rates up to 30p, five minute clips and 100Mbit rates, I’d recommend this approach over filming natively in 1080.

Above: Sony RX100 Mark V movie quality, coverage matched: 1080p (left), 4k (right), 100% crops

Now for some more sample movies, all in lovely 4k resolution.

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only)

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 V sensor

Like many premium compacts, the Sony RX100 V is equipped with a 1in sensor delivering 20 Megapixel images. But while most rivals are most likely using an older generation of the sensor, Sony keeps the latest versions for its own cameras. Most notably the sensor in the Mark V not only inherits the stacked design of the sensor in the Mark IV, but now also included embedded phase-detect AF points.

On most 1in sensors, including Sony’s RX100 Mark III, the signal processing circuit is on the same layer as the imaging pixels and the DRAM memory is set apart from the sensor. On the Mark IV and Mark V sensor though, the signal processing layer is directly below the imaging pixels, and below that on another layer is the DRAM memory. Everything is integrated into these sensors, allowing them to operate much faster than before – indeed up to five times faster. It’s this speed that supports ultra-fast shutter speeds with minimal rolling shutter artefacts, quick burst shooting with minimal blackout and the High Frame Rate video modes.

On top of this, the Mark V sensor features embedded phase-detect AF points for confident refocusing and is accompanied by the front-side LSI circuit which allows longer bursts and extended HFR videos.

Throughout this review I’ve put each of the capabilities to the test and found the RX100 V delivers on its claims. Whether you actually need these enhanced features is up to you, but the Mark V can certainly do things which other compacts can only dream of.

Before moving on though, it’s worth re-iterating the core premise of the RX100 series, which is packing a larger sensor than most compacts into a body that will still just about squeeze into most pockets. The key is the 1in-type sensor, smaller than the APS-C and Micro Four Thirds sensors in most interchangeable lens cameras, but comfortably larger than the tiny sensors in most point-and-shoot compacts and phones. Indeed the 1in-type sensor has around 2.8 times the surface area of 1/1.7in sensors and closer to four times the area of 1/2.3in sensors. The result is cleaner images in low light and you can see how the quality measures-up in my results pages.

In terms of resolution, the 20 Megapixel sensor delivers images with 5472×3648 pixels in the 3:2 aspect ratio. It’s possible to also choose 4:3, 16:9 and 1:1 aspect ratios, although each involves a crop and a reduction in resolution. Three levels of JPEG compression are available, and you can also shoot in RAW with or without a Fine (medium quality) JPEG. Contrast, sharpness and saturation are applied via a selection of Creative Style presets, with each parameter being adjustable in a +/-3 step range.

Now it’s time to see how the actual image quality measures-up in my Sony RX100 V quality results. Or check out my Sony RX100 V sample images, or skip straight to my verdict!

Check prices at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, eBay or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book, an official Cameralabs T-shirt or mug, or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!