What happened to PCW magazine

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Personal Computer World magazine: 1978-2009

An Obituary (from a former Editor’s perspective)

Personal Computer World, Britain’s first and longest-running IT magazine, ceased publication on June 8th 2009 after 31 years in the business. Publisher Incisive Media cited “an unprecedented decline in advertising brought about by the ongoing recession, combined with diminishing newsstand sales”, and announced the August 2009 issue would be the last.

PCW as it was fondly known, documented the Personal Computer industry from its birth in the late Seventies when the term PC simply referred to a single computer dedicated to one person, as oppose to a machine based on IBM’s architecture and generally running Microsoft Windows. Indeed IBM’s Personal Computer itself didn’t arrive until the magazine was three years old.

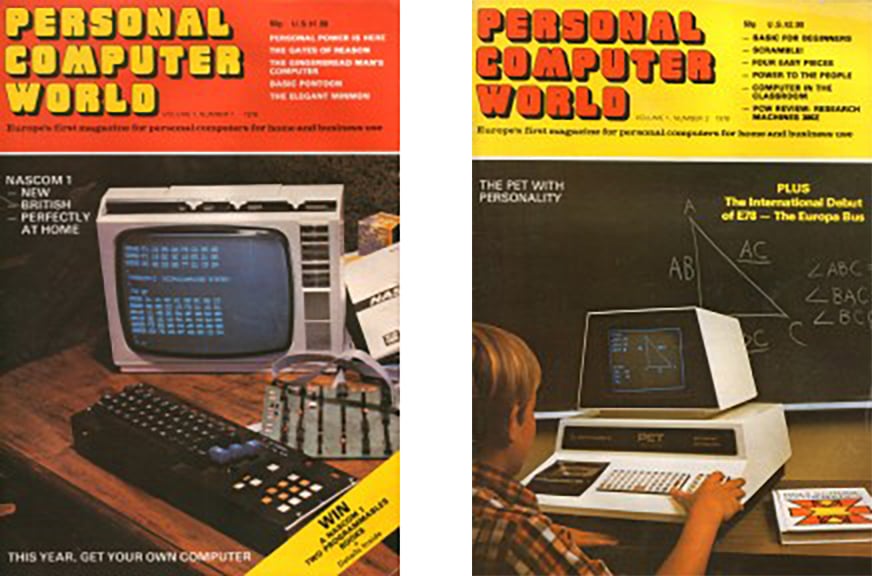

PCW’s first cover model was the NASCOM-1, a British home computer kit costing £197.50 and employing a 1HMz processor with 2Kb of RAM. NASCOM reckoned they’d need to sell 200 units to turn a profit, but they needn’t have worried. The computer shifted 400 units in its first fortnight alone, with an estimated 12,000 sold throughout its lifespan.

The potential of the NASCOM-1 partly inspired PCW’s founder, Angelo Zgorelec to launch the magazine. Zgorelec had been running a newsagent business in London when the thought occurred to him that rather than simply selling someone else’s publications, he could start his own. He’d always been interested in technology, but the subject of computers was inspired by a front page story in the Wall Street Journal prophesising how they were poised to take over the world.

Zgorelec had also been gazing fondly at a computer in the window of London’s first computer store, The Computer Workshop, but the big question was whether there was sufficient demand in the UK for a magazine about them, beyond that of US-import Byte. Zgorelec learnt Byte was holding a computer fair in New York, so he decided to take a look to judge demand. On arrival there was a two hour queue to get into the exhibition which told him everything he needed to know: if people were prepared to queue for two hours, personal computing was going to be huge.

Upon returning to London, Zgorelec secured distribution and asked his friend Miles Solomon to become the Editor of the new magazine, but what to call it? Zgorelec knew it had to be something ‘World’, but the term Personal Computer was far from main-stream – indeed it almost became Micro Computer World.

The first issue was timed to coincide with the launch of the NASCOM-1 in February 1978 and, reflecting the success of its cover star, sold out of its initial 30,000 copy print-run, going monthly from issue two.

PCW entered my own life from that very first issue, when as an Eight year old, I’d thumb through magazines in my local newsagent. I was interested in electronics, but the idea of assembling components into a computer yourself seemed utterly unbelievable. This was exactly the kind of subject matter of early issues, when owning a computer invariably meant building it, before learning how to program the thing.

The tide was about to change though with hobby kits quickly superseded by the first pre-built personal computers including the Apple II and, star of PCW’s second issue, the Commodore PET. The decade that followed was a unique period in the history of computing, with a multitude of personal and home machines battling for supremacy in a melting point that would shape the future IT industry.

During the early Eighties in particular it seemed a new computer was released almost every month. Machines from established technology giants were taken as seriously as models often developed by a handful of enthusiasts. It was this constantly evolving David and Goliath story which made PCW’s first ten years so compelling, with the magazine reporting on each and every new system, while also developing benchmarks to test them. Flying the flag for technology, PCW also sponsored an annual exhibition in London.

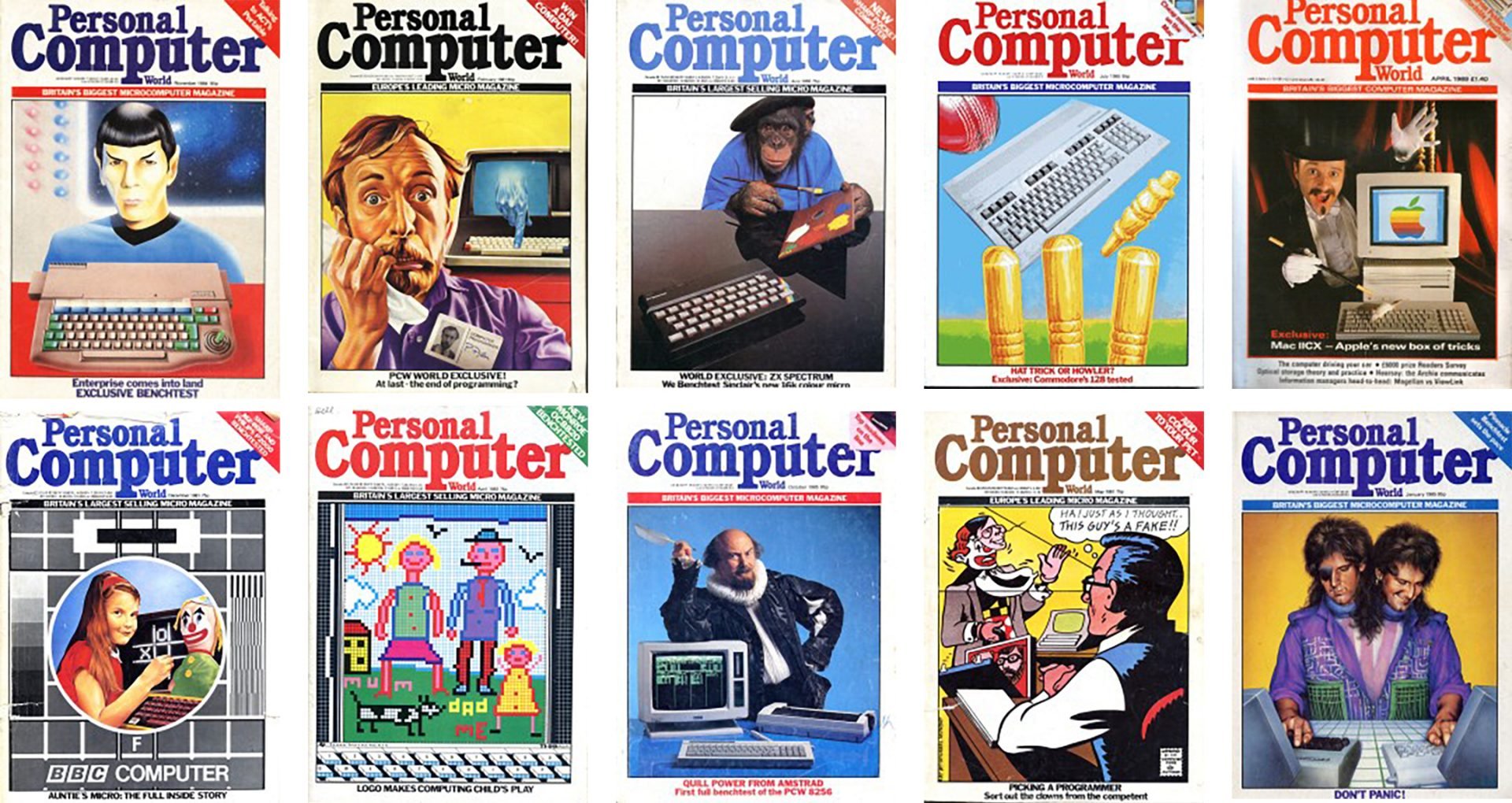

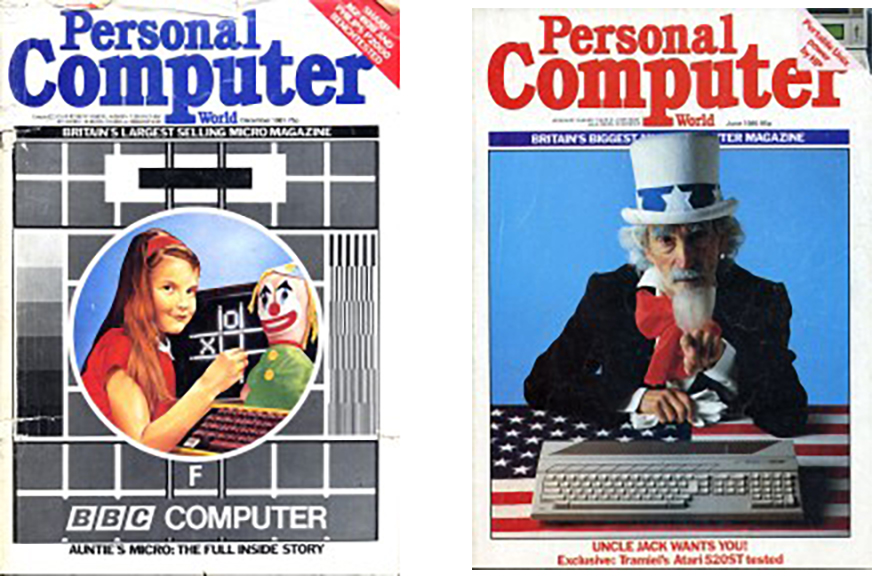

While pages of the magazine often featured technical diagrams and programming code, the cover artwork soon had a personality of its own.

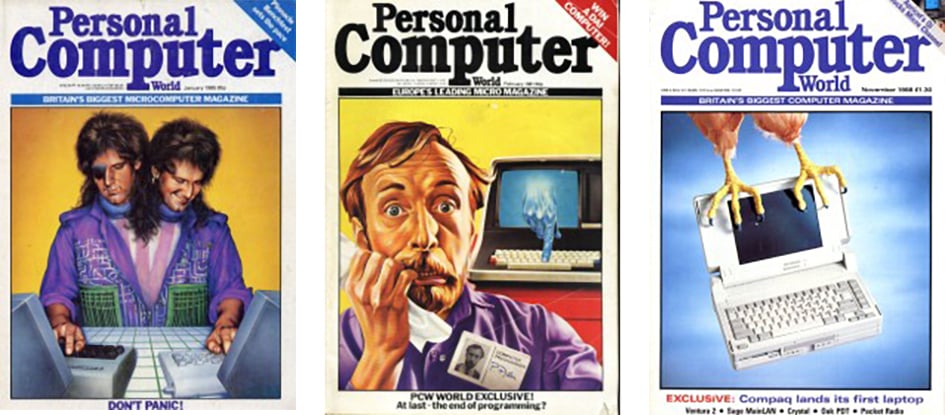

“Don’t panic!” cried the January 1985 issue with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s Zaphod Beeblebrox pictured operating two computers, with each head facing separate monitors.

Major software releases also became cover stars, with February 1981’s edition portraying a nervous-looking programmer fearing for his livelihood thanks to “The Last One”, a program which actually wrote its own programs.

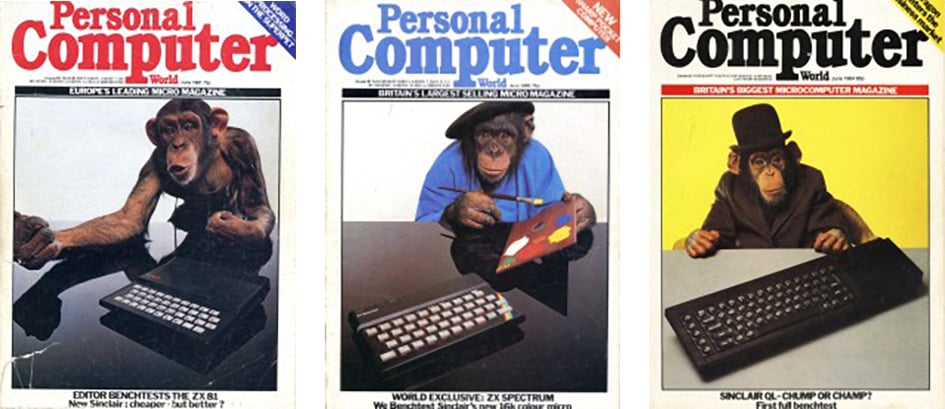

Some covers followed a cheeky theme: Sinclair’s ZX80 may have enjoyed a respectable cover portrait, but subsequent Sinclair computers were always accompanied by a monkey, later in costume: the ZX Spectrum’s cover monkey celebrated its colour capability by dressing as an artist with beret and palette, while the sophisticated QL’s monkey was a bowler-hatted business-simian. You don’t see that on many of today’s computer magazines (thankfully).

Due to its longevity, PCW also launched the careers of many IT journalists, my own included. I joined in the Summer of 1992, fulfilling a dream to work on the magazine I’d fondly read as a kid. Clones of the IBM architecture had already taken-over and Windows 3.1 about to arrive, but there was still plenty of evolution yet to take place. We may take full colour displays for granted today for example, but I remember reviewing one of the first 24-bit graphics cards, a Videologic Rapier 24, which due to the high price of memory cost the best part of three grand. My full-time stint at the magazine also coincided with the arrival of the first digital cameras, and as the only hobbyist photographer on the team, it fell to me to review them – so the Genesis of Cameralabs started at PCW back in the mid-1990’s.

The monkey covers may have long been history, but we still knew how to have fun. Every year we’d run a ‘five go mad’ feature where members of staff bought or built a computer system with the same budget, illustrated with parodies of popular movies. The Christmas issue was traditionally a special occasion with gift guides, retrospectives and a bumper quiz.

Along with news and reviews, PCW in the mid-Nineties continued to publish interviews with industry leaders, ran technology features and detailed reviews of new platforms including games consoles, along with puzzles and articles which looked at both the future and the past. The retro section was a particular favourite of mine which I later took over; indeed it was inspiration for my book Digital Retro which told the history of 44 vintage systems from the Seventies and Eighties.

Unlike the shorter reviews in today’s magazines, PCW also didn’t flinch from devoting several pages to key products in the early days, although Chris Cain’s heroic three-pager on a Logitech mouse (to fill an urgent gap) was arguably a step too far. I’d also be the first to admit some of the magazine’s content during this time could be described as a little self-indulgent, but it allowed it to stand out in what had now become a crowd on the newsstand.

While PCW was the first UK computer magazine by a long margin it now had a number of serious rivals, most notably in the form of Computer Shopper, launched in 1988, and PC Pro, launched in 1994. Both titles came from Dennis Publishing, coincidentally a former publisher of PCW before selling it to VNU.

While the heady days of varied home computers was now long over, the technology magazine industry itself was booming. PCW and its main rivals enjoyed circulations of around 150,000 issues a month, with the issues themselves regularly exceeding 500 pages and occasionally approaching 1000. Much of this was advertising, although it wasn’t uncommon to have over 200 pages of editorial.

Around that time, publishers would fondly discuss the ‘thud-factor’ as the heaviest issues yet dropped through your letter-box. I recall one reader complaining how the delivery of a particularly big issue had almost concussed his dog as it fell on the faithful pooch one morning.

As I became Editor in the late Nineties though, the tide was changing. Ad revenue remained pretty strong, but technical readers were increasingly drawn to highly detailed reviews published on the internet, in particular Toms Hardware and Anandtech, while my own beat of digital cameras was being very well-catered by dpreview, Imaging Resource and DC Resource. Magazine publishers also seemed to fear any kind of specialisation and instead favoured dumbing-down. PCW became increasingly schizophrenic, crying mainstream on the cover with bland PC group tests, while harbouring articles for the enthusiast at the back, as if hidden from the management’s gaze. Indeed it was in this very Hands On section that I contributed most of my subsequent work for PCW as a freelance writer from 1999 to the final issue – with a byline in every issue from 1992 to 2009, I may well have been the longest-running contributor.

While PCW would go on for another decade, I personally believe the contributing factors behind its demise were in place during the late Nineties. What made PCW an essential read during the first half of its life was the sheer variety of platforms covered in detail and a feature-lead style of reporting which included columns, regular interviews and even on occasion short stories.

Commercial demands saw much of this unique approach replaced by reviews and group tests which gradually dominated each issue. Coverage of alternative platforms was reduced and in some cases phased-out completely, and as time went on, PCW began to resemble its rivals which were often better-funded or equipped.

The reviews remained respectable, the news coverage, by industry veteran Clive Akass, was excellent, and the Hands On section remained a favourite with PCW’s regulars, but the magazine found itself directly competing against aggressive rivals for the same readers and advertising dollar.

Trying to sell a magazine as a buyer’s guide next to countless others doing exactly the same is hard enough, but when increasingly respectable websites are beating you to the big news and reviews with more detailed reports and a free cost-of-entry, well that’s a very tough sell. Incisive Media may blame the recession of the late Noughties for PCW’s demise, but the writing was on the wall a decade earlier when PCW started fighting for a slice of an ever-diminishing pie.

Of course commercial demands drive any successful business, and while it’s easy to criticise PCW for becoming homogenised with its rivals, could it have done any better as a general technology title, eschewing PC group tests for features about the industry and the people behind it? Something like a more computery-version of Wired for example, although perhaps that question has already been answered as an actual UK version of Wired launched and failed in the mid-Nineties, although recently relaunched again in 2009. Maybe this sort of material is best left to the Americans with their boundless enthusiasm for innovation and a significant portion of the technology industry on home ground.

Unless PCW is resurrected in a different form or medium, I guess we’ll never know if such an approach could work. At the time I wrote this, a few days after news of the magazine’s closure, the future of the name itself was uncertain, although the website remained active.

One thing’s for certain though: PCW was one of a kind. Unlike many publications, it attracted staff and contributors who were truly passionate about the subject matter and the magazine itself. The readers were equally passionate, and having dealt with enquiries on several different magazines, I can tell you they were a unique bunch. Many computer magazine readers would phone to complain about a problem with the cover disc, but only a PCW reader would then tell you how to fix it. It will be as frustrating for them to find PCW suddenly absent from the shelves without explanation as it was for the final team not to produce an official farewell edition – although perhaps Incisive Media didn’t want a repeat of earlier sudden VNU closures where disgruntled staff understandably let rip on the final issue.

That said, I doubt it would have been a problem. Most PCW staffers remained committed to the magazine for a long-term, with many contributing for over 10 years. I ended up being part of it for almost 17 years, but even that wasn’t unusual. Some writers, including industry legend Guy Kewney, also returned to the magazine many years after being a key part of its original appeal. You see, working for PCW felt like being part of an extended family which was always around, and even if you went away for a while, it would reassuringly be there when you wanted to come back. Sadly that’s no longer the case. PCW, we’ll miss you

Gordon Laing

Gordon Laing was on the PCW staff from 1992 to 1999, became the Editor for two years, and contributed as a freelancer every month until its closure in 2009. He’d like to thank Editor Guy Swarbrick, dep-ed Simon Rockman and Publisher Kit Gould for giving him his first break in 1992, Reviews Editor Chris Cain for showing him the ropes (and the sandwich shops), along with production Editor Lauraine Lee and Art team Darrell Kingsley and Jon Mason for making his copy look good. He’d also like to thank the Editors subsequent to his departure who continued to commission him, especially the departing team which consisted of Editor Kelvyn Taylor, Associate Editor Clive Akass and Production Editor Debbie Oliver. Gordon also made many close friends while working on the title – you know who you are!

Acknowledgements: thanks to the wonderful Centre for Computing History website for its large collection of early PCW covers. Thanks also to Rob Blincoe for his excellent interview with PCW founder Angelo Zgorelec, published in the 20th Anniversary edition of PCW.

PS – if you loved computers of the 70s and 80s, don’t forget to check out my coffee table history book: Digital Retro!